都市の農地はいつも翻弄されてきた。一所懸命に開墾して農業を営んでいたところを、戦後の農地改革(GHQ・1947)と農地法(1952)によってまとまった農地は解体され、零細な農業を構造的に強いられた。市街の開発圧力が高まる高度経済成長期には都市計画法(1968)により、都会となるべく市街化区域と田舎となるべく市街化調整区域が定義され、都市と農地の分離が進められた。いよいよ都市農地の存続が苦しくなったバブル崩壊の頃、生産緑地法(1992)の税制措置により都市農地は生産緑地化か賃貸住宅建設の2択を迫られ、地主は先祖代々受け継いできた農地を切り売りして賃貸経営をすることで収入を確保した。しかし、人口減と高齢化の目立つ近年になってようやく開発圧力が弱まり、今更ながら食料・農業・農村基本法(1999)や都市農業振興基本法(2015)において都市農地の環境保全・景観性、防火・避難、農業啓蒙・教育の機能が見直され、生き残った都市農地を保全する政策に転換した。都市農地は細かく刻まれ、まだらに市街化し、最終的には延命されることで今日に至っている。営農者からすると農業政策に振り回されたつらい歴史であるし、開発者からすると残念な街とみえるのかもしれない。

しかし都市計画学者からすると、農地混じりの都市は理想の都市であった。産業革命により自然から疎外されたイギリスの都市を憂いたE.ハワードの田園都市(Garden City・1898)の提案は自然との共生・職住近接が核であり、田園都市レッチワース(1902)を建設した。(東京でも渋沢栄一が田園都市を建設したが、ここに田園はほとんどなく、緑豊かな住宅地にとどまった。)農地混じりの都市は羨まれる理想の都市なのである。そこでは太陽と雨を受ける土で野菜が育ち、そこに住む人々が手にとって食べ、自然資源の循環を実感して生きることができる。生きた心地のする都市なのである。そうした農地混じりの都市が、東京西部の東久留米にもある。

その東久留米にて、野菜の直売所の設計と建設をすることになった。ここであらためて直売所を観察すると、直売所の原則が見えてきた。まず、野菜を供給する畑と人の通る道の境界にあって、野菜の世界と人の世界を出会わせている。また、農産施設であるために機能的かつ簡便であるので、仮設的で装置的・安価で自作可能であり、意匠を凝らしてはいないが立地と清廉さによるモニュメンタリティーをもっている。畑の野菜を置き・人が手に取ることを真面目に実現している。新しい直売所もこうした直売所の原則を引き受けるべきだろう。

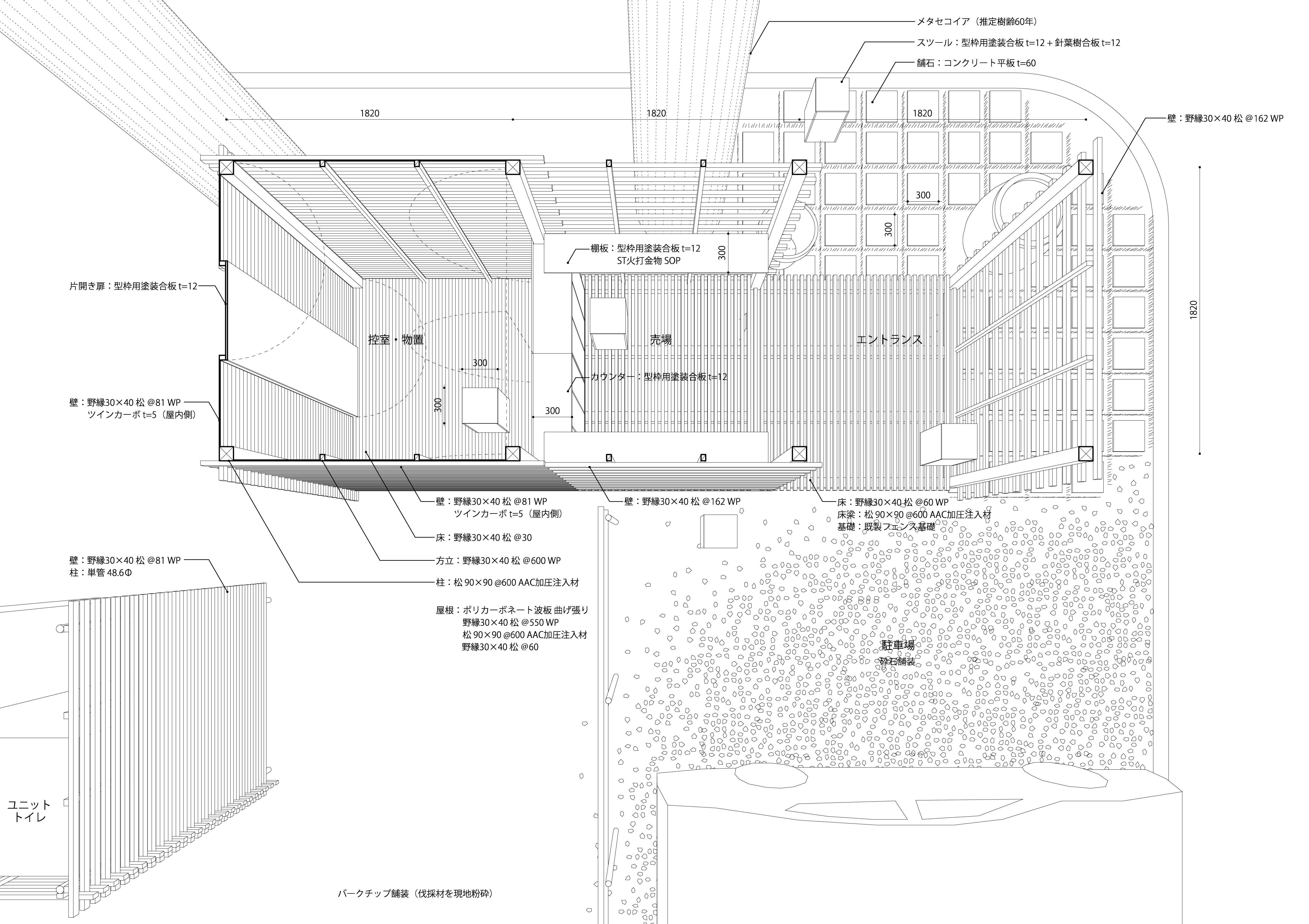

新しい直売所は90×90mmの防腐処理松材のフレームに30×40mmの松材タルキを纏ったかごのようなものとした。タルキによる工法は近所で施工した野菜・本・カフェ・イベントを扱う複合施設「MIDORIYA」で使っており、地域のアイコンとしてすでに認知されている。直売所の平面は1.8×5.4mで天井高さ1.8mの直方体で、野菜にとってはゆったり、人にとってはギリギリの寸法に設定して、野菜が主の家に人がお邪魔するような感じとした。平面は3マスの正方形からなり、道から見て手前のマスは入口、中央のマスは無人販売のときの野菜置場、奥のマスは体験農業の窓口や対面販売のときの受付として、機能に応じて徐々に壁のタルキの密度が増していく。壁と同じく天井と床もタルキを目透かしに並べて、フレームとの交点に複数本のビスを打って偶力を負担し、かごのように透けながらも剛性のある面の組み合わせとして構造を成り立たせている。直売所のすぐ横には樹齢50年高さ20mのメタセコイアが根を張っているので、基礎はフェンス用の独立基礎として、根を傷つけないように注意を払った。遠くから見える大きなメタセコイアに近づくと、木のかごが少し浮いて転がっているのが見える。家具はこぶりな300mmのモジュールで計画し、黄色いパネコート(型枠用塗装合板)で作った。直売所の入口から広がるペーブメントも300mm角のコンクリート平板である。かごにしまっておいた家具や平板をかごの内外に散らばらせて、野菜を置いたり人が立ち寄ったりできる場所をつくったようにした。

直売所は小さいけれども、農業や住む人々の世界を引き受けたり、直売所の原則を引き受けて地域の直売所ネットワークに参加したり、ささやかなモニュメンタリティーをもたせることで、点的な施設が場所と歴史に根ざして大きなインパクトをもつようになっていれば良い。

設計 IN STUDIO(小笹泉、奥村直子)

施工 基礎とフレーム:シグマ建設 その他全て:奈良山園、IN STUDIO(小笹泉、奥村直子)

設計期間 2018.8-2018.12

施工期間 2018.11-2018.12

写真 関口秀樹(ドローン写真)、小笹泉(他)

Farmland in cities has always been at the mercy of the landowners. After the war, the Agricultural Land Reform (GHQ, 1947) and the Agricultural Land Law (1952) dismantled the agricultural land and forced the farmers to farm on a small scale. During the period of rapid economic growth, when the pressure for urban development increased, the City Planning Law (1968) defined urbanized areas to be urban and urbanized control areas to be rural, and the separation of urban and agricultural land was promoted. At the time of the collapse of the bubble economy, when the survival of urban farmland finally became difficult, the tax measures of the Production Green Land Law (1992) forced urban farmland to choose between production green land and the construction of rental housing, and landowners secured income by selling off the farmland they had inherited from their ancestors and managing it as rental. However, in recent years, with a declining and ageing population, the pressure for development has finally weakened, and the Basic Law on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas (1999) and the Basic Law on the Promotion of Urban Agriculture (2015) have reassessed the functions of urban farmland in terms of environmental protection, landscape, fire prevention and evacuation, and agricultural awareness and education. The urban farmland has been carved into small pieces. Urban farmland has been chopped up into small pieces, urbanised and eventually prolonged to the present day. For the farmers, it is a painful history of agricultural policy, and for the developers, it may seem like a disappointing city.

From the point of view of urban planners, however, the city with its mixture of farmland was the ideal city. E. Howard's proposal for a Garden City (1898), which was based on the idea of living in harmony with nature and close proximity to work and housing, was based on his concern that British cities had become alienated from nature as a result of the Industrial Revolution. (In Tokyo, Eiichi Shibusawa built a Garden City, but it was little more than a green residential area. A city mixed with farmland is an ideal city to be envied. It is a city where vegetables grow in soil that receives the sun and the rain, where people can eat with their hands, and where they can live with the cycle of natural resources. It is a city where you feel alive. Such a city with mixed farmland can be found in Higashikurume in western Tokyo.

In Higashikurume, we were asked to design and build a direct vegetable market. Observing the market again, the principles of the market became clear to me. First of all, it is located at the boundary between the field where the vegetables are supplied and the street where people pass by, so that the world of vegetables and the world of people meet. It is also functional and simple because it is an agricultural facility, it is temporary, simple, inexpensive and can be made by oneself. It is a serious attempt to put vegetables from the fields in the hands of people. The new market should take on these principles.

The new market is made up of a 90 x 90 mm frame of preservative treated pine wood, covered with 30 x 40 mm timber. This method of construction is used in the nearby MIDORIYA, a complex selling vegetables, books, a café and events, and is already recognised as a local icon. The floor plan of the market is 1.8 x 5.4m with a ceiling height of 1.8m. The front square is the entrance, the middle square is the vegetable storage area for unattended sales, and the back square is the reception area for hands-on farming and face-to-face sales. The density of the wall tiles gradually increases according to their function. As with the walls, the ceiling and floor are also made of openwork, with multiple screws at the intersections of the frames to bear even forces, making the structure a combination of transparent but rigid surfaces like a cage. A 50-year-old, 20-metre high metasequoia tree has its roots right next to the shop, so the foundations were designed to be independent of the fence, taking care not to damage the roots. As you approach the large metasequoia from a distance, you can see the wooden cage floating and rolling a little. The furniture is planned in small 300mm modules, made of yellow panelling (painted plywood for formwork). The pavement that extends from the entrance to the shop is also made of 300mm square concrete slabs. Furniture and slabs stored in baskets are scattered inside and outside the baskets to create a place where people can place their vegetables and stop by.

Although the market is small, it is hoped that by taking on the world of agriculture and the people who live there, by taking on the principles of the market and participating in the local market network, and by giving it a small monumentality, the point-like facility will have a big impact, rooted in place and history.

Design : IN STUDIO (Izumi Kozasa and Naoko Okumura)

Construction : IN STUDIO (Izumi Kozasa, Naoko Okumura), Client

Design period : 2018.8-2018.12

Construction period : 2019.12